The Open Country podcast on Radio 4 for 13 September 2012 (i.e. 9 years ago) involved a visit to the Moray Firth, checking on the health of its marine mammal population.

The beaching of 26 pilot whales in Fife had made the headlines shortly before that and the programme also included discussion of a previous beaching of about 77 pilot whales near Durness in Sutherland.

These events highlighted the importance attached by many of us to the creatures which live, largely unobserved, in the seas around our shores.

This radio-programme-as-podcast was trying to figure out what it is about these creatures which strikes such a chord with us humans.

The presenter, Richard Uridge, begins the programme having just stepped aboard a RIB (a ‘rigid inflatable boat’).

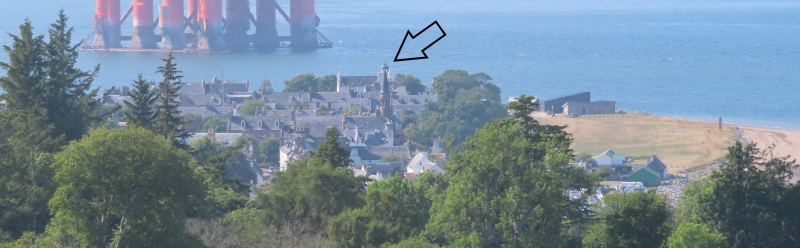

Although there is no real explanation of where he is exactly and who he is travelling with out onto the Moray Firth, we can deduce that he is in the village of Cromarty on the Black Isle.

We can also figure out that he is on a trip with Ecoventures.

Ecoventures specialise in leading wildlife-watching trips using a custom-built 9.5 m RIB.

On their trips, they frequently encounter the resident colony of bottlenose dolphins, harbour porpoise, minke whales, seals and a wide variety of seabirds.

Ecoventures has operated from Cromarty since 2004 and is owned and operated by local skipper, Sarah Pern.

As the trip begins, there is a palpable sense of anticipation. The skipper, Sarah Pern, is just casting off the rope and moving the boat away from the pontoon, before the engines rev up.

As Sarah explains, the bottlenose dolphins in the Moray Firth are the biggest, fattest dolphins you would see anywhere in the world.

What you’re looking for is something that is about 3.5 to 4m in length.

They weigh about 350kg.

Even if a dolphin is just surfacing quietly, they will show quite a bit of their body to any observer. You will see a good bit of the fin and the back.

if they are jumping and landing, on the other hand, you will just see a big splash!

You tend to see them in groups – anything up to about 20 in a pod is common. There are about 200 dolphins which are thought to regularly inhabit the waters of the Moray Firth.

They have a sighting of some porpoise.

Again, as Sarah explains, porpoise are from the same family as dolphins but are a lot smaller.

You will quite often just get 2 or 3 little ‘surfaces’ by them and then a slightly longer dive, out of sight. You have to be a bit patient sometimes with porpoise.

If there is any wind at all, disturbing the surface of the sea, porpoise can be difficult to see at all.

Porpoise don’t show a lot of the body, as they surface. They have quite a small, triangular fin.

It’s quite difficult to individually identify propoise as well. Dolphins are much, much easier to tell apart. They are also much easier to spot, in general.

You tend to find porpoise are much less inclined to interact with the boat.

Sometimes they will, but generally they are a little bit shyer and a little bit harder to get close to.

Dolphins are not always inquisitive of the boat – it depends what they are up to at the time.

Ecoventures is an accredited operator with the Dolphin Space Programme, a voluntary initiative set up by a number of local organisations to safeguard the welfare of the cetaceans in the Moray Firth. As a result, in manoeuvring the RIB, Sarah tends just to approach the dolphins to a distance at which they do not feel threatened or intimidated and then it is up to the dolphins whether they want to come closer to the boat or not. More often than not, dolphins will choose to engage with you.

As Sarah says, it can be quite difficult to enthuse people about porpoise. They don’t tend to interact with the boat to the same extent as dolphins. People don’t feel that same connection. Because dolphins are actually choosing to spend time with you, to check you out, people respond to that.

Taking people on dolphin-watching trips is a rewarding job.

The best bit of the work for Sarah is that, in terms of ‘positive’ reactions from those on Ecoventure trips, you get everything from people ‘crying on your shoulder’ to screams of delight.

It’s great to see that ‘obvious’ kind of reaction and enthusiasm.

And then you get the other ones – still positive – who will get off the boat and not really say very much – perhaps just say “thank you” before they head off. But then, later, you get a letter or an email saying it was the most fantastic day of their life. They’re just not as exuberant about it on the boat. You do see ‘everything’ in terms of the variety of people’s positive reactions.

The programme then swtiches focus from the east end of the Black Isle at Cromarty to its south side, nearer to Inverness and close to the village of Fortrose. It’s time to meet another cetacean enthusiast…

Charlie Phillips studies bottlenose dolphins for the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, as a field officer.

Charlie explains that the peninsula which ends with Chanonry Point dominates this part of the landscape – or “coast-scape”, if you like.

The narrow stretch of water between Chanonry Point and Fort George tends to act as a a ‘funnel’.

The tidal conditions here can get fantastically strong. The dolphins know this and, as one demonstration of their intelligence, they use it almost like a supermarket conveyor belt.

Cleverly staying in the one position, the tide sweeps the food to them. In other words, the question might be: why waste energy chasing after your food if you can wait for the tide to bring your food to you? It’s the dolphins’ intelligence at work.

On that day, there were about 20 people gathered in small groups on the shingle looking out into the narrows between Chanonry Point and Fort George.

Charlie Phillips explains that what they’re all looking for is the approach of dorsal fins.

On a calm day such as this one, they’re looking for the little puff of breath as the dolphin comes to the surface – and maybe the tip of a dorsal fin. If there’s any youngsters with the adult dolphin, you might see them having a little scurry about beside their mother.

You just have to keep your eyes open and see what happens.

As Charlie says, we are getting a brief look into the dolphins’ realm and you don’t even need to get wet to do it.

Because of the dolphins’ proximity to the shoreline at Chanonry Point – where people can almost come in contact with them, perhaps as little as 10-15 feet away – it can be a pretty special experience.

Bottlenose dolphins have good eyesight, both underwater and above the surface.

Charlie Phillips explains that, from Chanonry Point, they see the “A-Z” of behaviour of the bottlenose dolphins. Everything from resting to hunting salmon at top speed.

You’re able to watch what dolphins do and what they do best.

Sometimes the behaviour can be difficult to interpret.

Sometimes you have to try not to let your imagination run away with itself (perhaps because, sometimes, their behaviour towards theire prey can seem almost cruel).

You’ve got to try and just look dispassionately at what’s happening.

While Charlie is looking through his long lens at the dolphins and taking the photographs he needs to take, he has to “switch off” slightly. But he still gets excited by his job.

The dolphins at Chanonry Point have a different ‘menu’ depending on the season.

The dolphins’ behaviour changes to accommodate this.

At the end of the salmon season, for example, mackerel and herring become more prevalent.

You can tell that from the increased numbers of gannets in the vicinity, plunge diving for the same prey.

This also changes the way that the dolphins have to hunt.

They must hunt more in a cooperative manner than the individual approach of “one dolphin, one salmon”.

You find groups of dolphins corralling shoals of herring and then leaping into the middle of the shoal to pick off what they can. It’s amazing to see. There seems to be some sort of planning involved in the process and the dolphins then have the ability and intelligence to execute on those plans in hunting shoals of fish. They are cooperating and communicating all the time.

There is now underwater footage available of this kind of manoeuvring by dolphins which is just breathtaking to see. It gives us a better understanding of how complex and wonderful they are.

The programme then switches its attentions back to Cromarty village for its next interview.

Cromarty Lighthouse houses the Aberdeen University Lighthouse Field Station research team.

Professor Paul Thompson and his colleagues assess the well-being of the marine environment.

In terms of how well the bottlenose dolphin population is doing in the Moray Firth, in many ways, “we just don’t know”.

It’s difficult even to estimate how many animals there are in the first place, let alone how that has changed over the years.

They’re doing better than the scientists thought they were a few years ago.

Beaching or stranding of marine animals is more difficult to interpret.

On the one hand, if there were ‘more’ animals out there, you would expect more beachings.

In some cases, beachings have been blamed on things like naval exercises but research also shows that these things occur naturally anyway.

In the past, whale strandings were ‘popular’ events for the local community, possibly providing meat and blubber for the winter store.

Any large whale beached is principally the property of the Crown. That’s why strandings have been reported to the coastguard for the last hundred years at least.

We don’t really understand why bottlenose dolphin population is currently holding steady and possibly even increasing. It’s hard enough to know whether the populations are growing up or down without then having to try to understand what factors might be at play in affecting the changes. It could be natural variation in food supply. It could be things that humans are doing to the environment.

The more information you have about the life history and the food requirements of these animals, the easier it is to think of methods by which we can help protect their environment.

Protecting their environment will maximise the dolphins’ chances of having a sustainable population.

But, in Professor Thompson’s opinion, as marine conservationist, we should not let the lack of full information prevent us from coming forward with ‘good ideas’ for mitigations which will help the marine animals in their environment.

A ‘precautionary’ approach is best.

Sometimes you have to avoid making changes even if there is not a clearly demonstrated adverse effect from that type of change, historically.

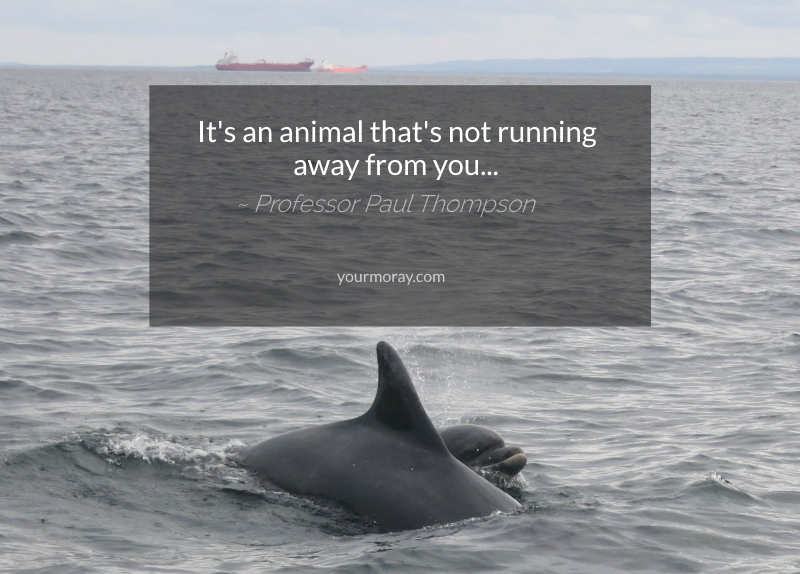

The Professor considers that the fact that these are animals “which are not running away from you” is important to our feelings towards them as humans.

The fact that it is so relatively easy to go out “into the wild” and see and interact with bottlenose dolphins explains a lot about why they mean so much to us.

Not only is it a great experience to be watching wildlife like that, generally, the dolphins themselves – because of their distinguishing features on their bodies – can be known to us as individuals. For some of the dolphins, the Aberdeen University study has been ‘working with’ them for over 20 years. (For some of the female dolphins, they know how many calves they have had. And they know how many calves their calves have had).

The fact that, on the one hand, you know some much about them but, on the other hand, know there is still so much more to be learned about them is really exciting.

Barbara Cheney – a Research Fellow at the Aberdeen University Lighthouse Field Station – discusses the naming and numbering of dolphins as part of their study of the local bottlenose dolphin population.

Example names are Zephyr; Talisman; Gee; and Guinness.

The researchers can recognise the individual bottlenose dolphins from the markings on their dorsal fins.

Some of the markings – described as ‘rakes’ on the dorsal fin – are teeth marks caused by other bottlenose dolphins.

Some of the dolphins’ markings can be skin lesions and scientists are not exactly sure what causes these. They seem to be either viral, bacterial or fungal infections. All bottlenose dolphin populations have such apparent health problems. It is akin to humans having eczema or acne. The skin conditions seem to be more prevalent than average among the Moray Firth bottlenose population but the reasons for that are not clear. The majority of the Moray Firth dolphins have some form of skin lesions.

Although young dolphins have less dorsal fin markings and are therefore harder to track, they tend to stay with their mothers for about 3 to 6 years from birth. In the early part of their lives they have a very close association with their mother.

The researchers number every single dolphin but also try to give them names to make it easier to recognise them.

They often try to give each dolphin a name which is linked to the marks on their fin.

But there are also some ‘random’, fun names thrown in as well.

Referring to “Sailfin” (dolphin number 8), a large adult male, he has probably the biggest fin that has been seen amongst the Moray Firth dolphin population.

With around 10 to 15 recorded sightings of him per year, he’s a well-known character.

Dolphin number 129, on the other hand, is not seen nearly so often. Sightings of “Girder” are relatively infrequent: maybe once or twice a year. They think he is a male dolphin but that’s only because he has never been seen with a calf. So they’re not 100% sure even of this dolphin’s sex. It can be especially difficult to recognise the male animals.

The home page of Charlie Phillips’ website has useful illustrations of dolphin dorsal fin markings. At the link, you have to scroll down to the cross-head “The Science behind the photographs….” and the photos below it.

Cetaceans are mysterious and intriguing to us given that they spend so much of their lives underwater.

Dolphins are very social animals.

They are said to have a “fission/fusion” society. They ‘mix and match’ a lot. The groups are constantly changing. The individuals are constantly hanging out with different animals.

On the other hand, you do see a few family groups spending time together. When calves get a bit older, they may leave their mums but then come back later and again spend time with them.

Bottlenose dolphins have a complicated social structure which is not yet fully understood.

Join our Newsletter for a weekly Moray update.

Delivered straight to your inbox. (See the sign-up form below).