On BBC Radio Scotland’s “Out of Doors” programme for Saturday, 20 February 2021 they were talking about drainage and how large parts of the north-east of Scotland did not previously exist as land.

They explained how, beginning about 1000 years ago, one particular part of Moray had changed beyond all recognition in the intervening period.

Here’s a brief history of local land reclamation in Moray.

It was August, in the year 1040.

As the early morning sea mist cleared, the captain scanned the horizon, looking for the other 4 boats of the invading force. To starboard, the island of what was to become “Lossiemouth” loomed out of the haar.

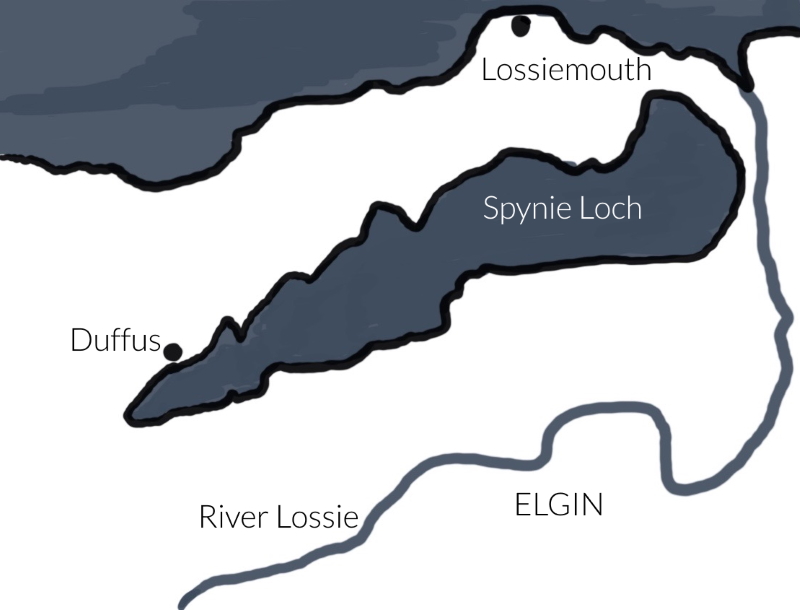

Slowly, the captain edged his ship through the narrow gap and into the massive sea loch, south to Spynie, the port of Elgin.

There, he anchored and waited.

Ghost-like, one by one the other ships of the fleet arrived. In the shallow waters that stretched before them, the skippers of the other ships lowered small boats and joined the others at the stern of the main ship to hold a council of war.

King Duncan outlined his plans for the coming battle against his cousin, Macbeth.

Duncan was to die on the battlefield at Pigaveny, near Elgin, and Macbeth took the throne.

Spynie, the port of Elgin, continued to thrive.

Spynie Loch provided a safe anchorage for fishing boats and merchant ships.

Over the years, the entrance to the loch slowly silted up and, by the Middle Ages, navigation was virtually impossible.

As the extensive freshwater wetland evolved, many landowners surrounding the loch looked to land reclamation projects in Holland, Loch Leven and the Norfolk Broads with interest.

Around this time, Loch Leven had been lowered by around 4 1/2 feet to create additional land and wealth for those who owned ground by the water’s edge.

The Lairds and the Bishops of Moray were envious of these land creation schemes.

Already, along the coast at Loch of Strathbeg, a wind-powered pump was steadily lowering the waters to expose more farmland. The South Loch in Edinburgh had been drained in the 1720s to form the Meadows. Draining lochs was high fashion and very lucrative.

Thomas Telford was consulted in 1808.

The plans were to construct a canal to drain this vast area which is now rich farmland and home to RAF Lossiemouth. At that time, though, any runways would have found themselves well underwater.

At a cost of £12,000, one of the men who constructed the Caledonian Canal, Mr William Hughes, created the channel which would drain Spynie Loch, with a small amount of wetland retained for sporting purposes. The landowners gained 2,500 acres of fertile land, with some left for angling and wild fowling for the landed classes.

The Telford design was elegant.

Sluice gates at the end of the Spynie Canal opened when the tide was going out to allow drainage and were closed by the incoming waves to prevent the land being re-flooded.

It was an ingenious system which lasted for well over 100 years until the authorities decided that a simple and environmentally energy-neutral system needed to be replaced with powered pumps.

As the loch lowered, the town of Lossiemouth – or Branderburgh – once virtually an island, took on the role of port. In addition, there was a small settlement of 51 fisherman’s cottages, built at Seatown or, as it was known locally, “Dogwall”, due to the habit of drying dog skins which were used, when blown up, as floats for nets.

Is the Moray coast ‘boring’?

Those modern-day folk who like to sail in the Moray Firth may bemoan the fact that it’s not like the West Coast. There are no islands or sea lochs to explore.

But it’s all here. (It’s just hidden from view). This landscape – the airbase, the fields – are all man-made.

Were we to switch off the pumps and open the sluice gates, we could “reclaim” the waterways of the north-east, recreate the myriad of small islands, 2,500 acres of waterways, wetlands, and reopen the port of Elgin?

Maybe not. In fact, certainly not a serious suggestion if you’re living on the floodplain or you need to travel from Lossiemouth to Elgin (or vice versa) to get to your work.

Leave a Reply